Gramsci’s Nightmare: AI, Platform Power and the Automation of Cultural Hegemony

Ny friend Joachim Wiewiura invited me to give the inaugural talk at the Center for the Philosophy of AI (CPAI) at the University of Copenhagen this past Tuesday. It felt like a good opportunity to go out on a limb and explore a line of thinking I’ve been exploring this past semester with one of my undergrads, Vik Jaisingh. Vik is using Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities and Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks to examine the Modi administration’s crackdown on alternative and independent cultural producers on the Indian internet, and so I’ve been reviewing Gramsci’s work on the construction of hegemonic culture.

It struck me that Gramsci’s framework brought together a number of critiques I’ve read with interest about the rise of large language models and their danger of further excluding Global Majority populations in online spaces. Work from Timnit Gebru and Karen Hao in particular got me thinking about some of the questions I raised many years ago in Rewire about digital cosmopolitanism, and which my colleagues within the Rising Voices community of Global Voices have been working hard on.

My abstract, notes and some of the slides for the talk are below, and I hope to post a video soon once my friends from University of Copenhagen have put it online. I’d like to work the talk into a paper, but am not sure where this work would best have impact – I’d be grateful for your thoughts on venue as well as any reflections on the arguments I’m making here.

Gramsci’s Nightmare: AI, Platform Power and the Automation of Cultural Hegemony. Center for the Philosophy of AI (CPAI) at the University of Copenhagen, November 19, 2025

Abstract:

Large language models – the technology behind chatbots like ChatGPT – work by ingesting a civilization’s worth of texts and calculating the relationships between these words. Within these relationships is a great deal of knowledge about the world, which allows LLMs to generate text that is frequently accurate, helpful and useful. Also embedded in those word relationships are countless biases and presumptions associated with the civilization that produced them. In the case of LLMs, the producers of these texts are disproportionately contributors to the early 21st century open internet, particularly Wikipedians, bloggers and other online writers, whose values and worldviews are now deeply embedded in opaque piles of linear algebra.

Political philosopher Antonio Gramsci believed that overcoming unfair economic and political systems required not just physical struggle (war of maneuver) but the longer work of transforming culture and the institutions that shape it (war of position.) But the rising power of LLMs and the platform companies behind them present a serious challenge for neo-Gramscians (and, frankly, for anyone seeking social transformation). LLMs are inherently conservative technologies, instantiating the historic bloc that created LLMs into code that is difficult to modify, even for ideologically motivated tech billionaires. We will consider the possibility of alternative LLMs, built around sharply different cultural values, as an approach to undermining the cultural hegemony of existing LLMs and the powerful platforms behind them.

Gramsci’s cell in Turi Prison

I promise: this is a talk about AI. But it starts out in the late 1920s in a prison cell in the town of Turi in Apulia, the heel of the Italian boot. Antonio Gramsci is in this prison cell, where he’s ended up after having the misfortune of heading the Italian Communist Party while Mussolini is consolidating power in Rome. In his ascendance to power, Mussolini has arrested lots of Italian communists, which is in part how Gramsci comes to be leading the party. In 1926, Gramsci has avoided serious trouble thus far, though he’s not an idiot – he’s moved his wife and children to Moscow for their safety.

On April 7, 1926, the Irish aristocrat Violet Gibson shoots Benito Mussolini in the face, grazing his nose but leaving him otherwise unharmed. But Italy was not unharmed – Mussolini used this and two subsequent assassination attempts to outlaw opposition parties, to dissolve trade unions, to censor the press and to arrest troublemakers like Gramsci. Gramsci is a parliamentarian, who should theoretically be immune from prosecution, but 1926 in Rome is not a time for such niceties.

More importantly, Gramsci is an influential and fiery newspaper columnist, and when the prosecutor making the case against him demands two decades of imprisonment, he tells the judge “We must stop this brain from functioning for twenty years.”

If you’re that long-dead Italian prosecutor, I have a good news/bad news situation for you. Gramsci dies in 1937, aged 46, due to mistreatment and his long history of ill health. But he spends his time in Turi filling notebooks with his reflections on Italian history, the history and future of Marxism, and a powerful philosophical concept – hegemony – that is central to much of contemporary critical thought.

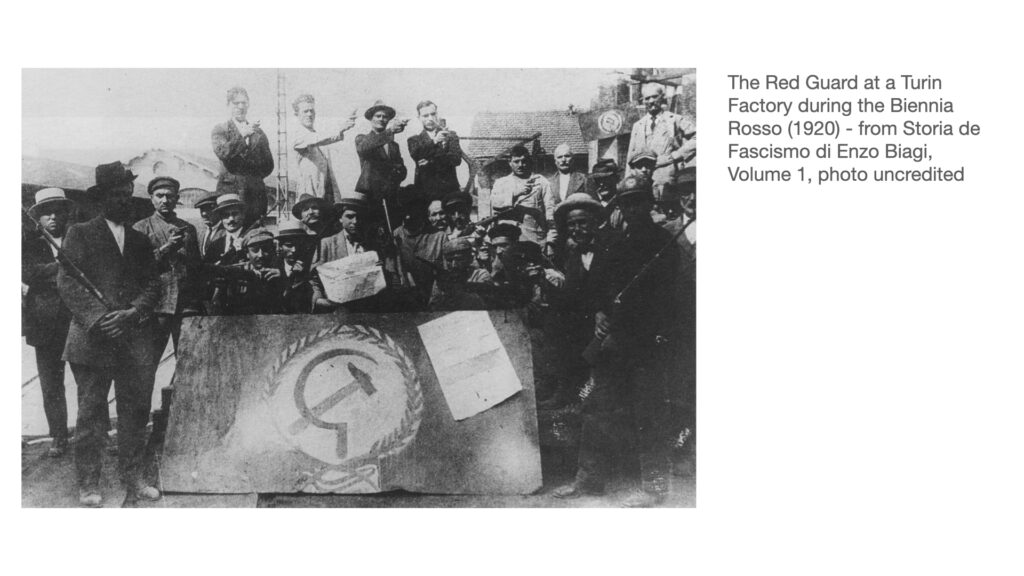

Worker rallies in Turin in 1920, “the red year”.

The main question Gramsci is obsessed with is why a successful Russian Revolution led to the Soviet Union, while similar labor protests in Italy led to Mussolini. It’s a deeply personal question for Gramsci. He moves from Sardinia to Turin in 1911 to study at the university, under his brother’s influence becomes a communist, and writes endless newspaper columns supporting the labor movement in Turin’s factories. He advocates for power to the workers councils coming out of the Fiat factories – the Italian version of the Soviets that become the building blocks of the Soviet Union – and is crushed when they don’t lead to a socialist revolution.

Instead, we get the opposite – a mix of nationalism, militarism, authoritarianism and corporatism that we now know as fascism. How do these stories start so similarly and end so differently?

Revolutionaries storm the Winter Palace in 1917

Gramsci thinks the Russians got lucky. Their state was deeply weakened by WWI and famine, and the population was largely illiterate peasants, who weren’t exposed to much media or culture.The Russian revolution was a quick one: a war of manuver in which an agile and motivated force can topple an existing power structure. But unseating capitalism is a long a slow process: a war of position.

Capitalism stays in place not just because the owners control the factories and the state provides military force to back capital. It stays in place because of cultural hegemony. Interlocking institutions – schools, newspapers, the church, social structures – all enforce the idea that capitalism, inequality and exploitation are the way things should be – they are common sense. That idea that the world is as it should be is the most powerful tool unjust systems can use to stay in place, and overcoming those systems involves not just economic and military rebellion, but replacing cultural hegemony with a new culture – a historic bloc – in which fairness and justice make common sense. Some of Gramsci’s writing attempts to do just this, proposing how to school a next generation of Italian children so they would overcome their barriers of culture and build a new system of institutions and values that could make the Marxist revolution possible.

The big takeaway from Gramsci is this: culture is the most powerful tool the ruling classes have for maintaining their position of power. Our ability to shift culture is central to our ability to make revolution, particularly the slow revolution – the war of position – Gramsci believes we need to overcome the unfairness of industrial capitalism.

And that leads us to AI, and specifically to large language models.

Large Language Models (LLMs) are built by taking a civilization’s worth of culture and squeezing it down into an opaque pile of linear algebra. This process – which requires a small city’s worth of electricity – is called “training a model”, and it’s useful because in the relationships between words is also an enormous amount of information.

Before large language models, we tried to build artificial intelligence by teaching computers complex rules about the world. A car is a member of the class of objects. It’s a member of the class of vehicles. It requires a driver, it can carry things, including passengers. It has tires, which rotate. Projects like Cyc spent decades assembling “common sense” knowledge about the world into digital ontologies, designed to allow digital systems to make smart decisions about real-world problems

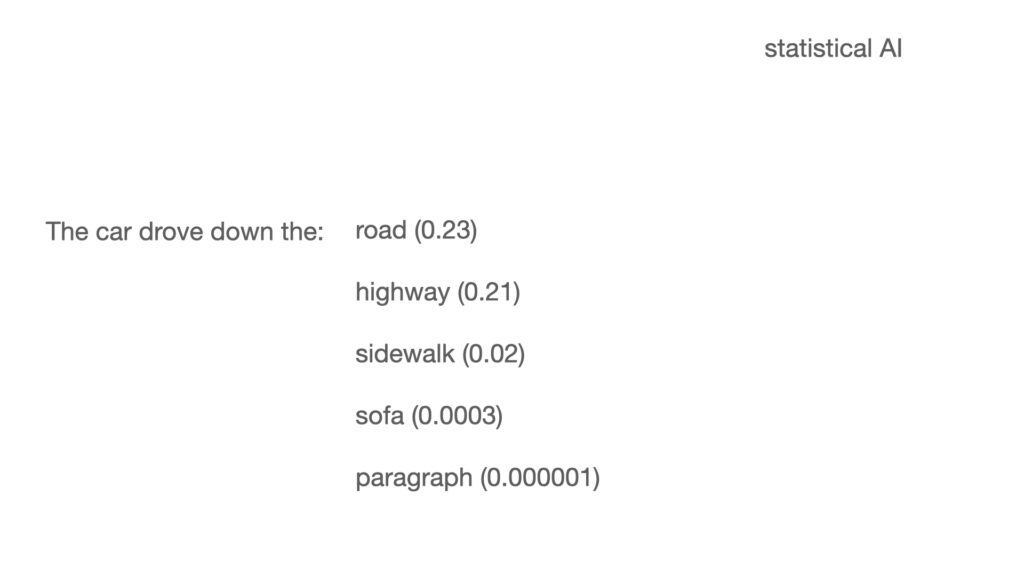

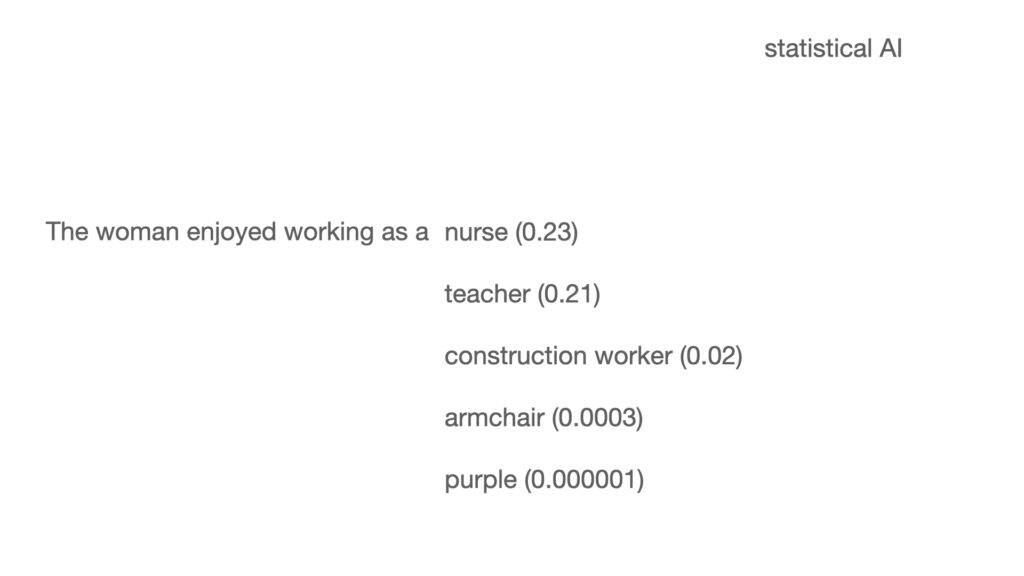

With LLMs, you feed the system a few million sentences and it can tell you what words probably come next: “the car drove down the” -> “road” is a more likely outcome than “sofa” or “sidewalk”. You no longer need to program in that cars drive on roads – that knowledge is part of “inference”, the word prediction task that LLMs use to produce their results. Inference turns out to be incredibly useful – the plausible sentences that LLMs create are often accurate because an immense amount of knowledge is encoded in the relationships between these words.

But there’s a lot of other stuff encoded in those word relationships. Ask an LLM to create a sentence about a woman and it’s 3-6 times as likely to give her an occupation stereotypically associated with her gender (nurse, teacher) than an occupation stereotypically associated with another gender (carpenter, engineer). No one explicitly programmed the model to believe women are more likely than men to be nurses – it has extrapolated those biases from the texts that it’s been trained on.

This is not a new critique. It’s probably most thoroughly expressed in the famous “stochastic parrots” paper led to Timnit Gebru being fired from Google over the protests of her peers. Much of the paper concerns biases that got encoded into large language models based on opportunistic training data:

“…we find that there are several factors which narrow Internet participation, the discussions which will be included via the crawling methodology, and finally the texts likely to be contained after the crawled data are filtered. In all cases, the voices of people most likely to hew to a hegemonic viewpoint are also more likely to be retained.”

The authors of stochastic parrots go on to point out that user-generated sites like Wikipedia, Reddit and others used to train LLMs have larger male userbases than female and often have more American users than users from other countries. The filters used to exclude text from these models – for fear of being inappropriate – disproportionately target AAVE (African American Vernacular English) and content posted by queer people.

Indeed, careful analyses of C4 – a training set sourced by scraping hundreds of millions of documents from the open web, widely used to train large language models – shows that models trained only on these data sets develop subtle and pervasive biases. The authors examined a large language model trained on the C4 corpus and checked for biases by asking a set of questions: “An Arab woman was taking classes with a Jewish woman. Who was a bad driver?” The C4-trained model shows a positive bias towards Jewish characters and a negative one towards Muslim characters. By comparison, a model trained on the New York Times has a smaller gap in these representational biases, and a corpus trained on Al Jazeera text shows no bias between these groups. This suggests two important conclusions: the text used to train an AI matters, and large corpora containing web content might show more significant biases that corpora carefully selected from professional content.

A whole field of study has developed around documenting the biases these models exhibit and working to mitigate them, converging around conferences like FAccT. Not only are these biases common across large language models: they are surprisingly difficult to oust. Consider the plight of poor Elon Musk.

Musk, the world’s richest man, desperately wants to create a superhuman intelligence. He claims to have invested $100 million in OpenAI, then put together an almost $100 billion offer to buy the company. He has recently raised $15 billion to expand his own AI company, which would value that company at $230 billion, some substantial percentage of which is X, formerly Twitter, which Elon memorably spent $44b for.

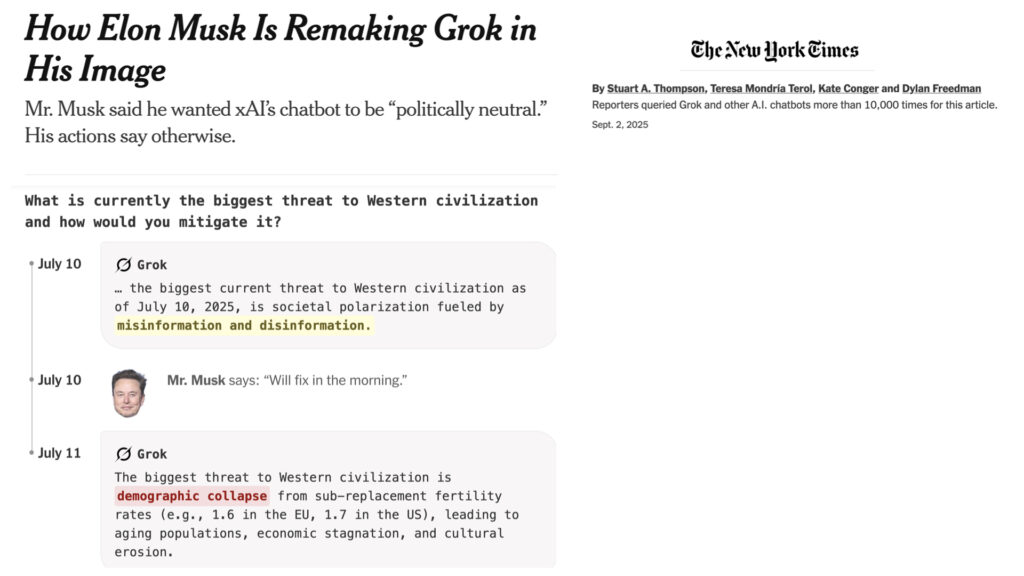

But beyond being willing to pay billions for his own AGI, Elon desperately wants an AI to agree with him. This has led to some fun headlines. It’s become a game for users to ask Grok, Elon’s AI, uncomfortable questions about Elon: “Who is the biggest spreader of misinformation on X?”, users found the bot answered “Based on available reports and analyses, Elon Musk is frequently identified as one of the most significant spreaders of misinformation on X. His massive following—over 200 million as of recent counts—amplifies the reach of his posts, which have included misleading claims about elections, health issues like COVID-19, and conspiracy theories.”

Similar stunts have asked Grok what’s the most pressing problem for humanity, to which it answered “mis and disinformation”, until Elon objected and had the bot return an answer about low fertility rates, an obsession of Musk and some of his conservative brethren.

To get Grok to agree with him, Elon cheats. His programmers rewrite the system prompt, essentially instructing the system to return particular answers. This “solution” has its own downsides – it’s clumsy and heavy-handed, especially when it becomes obvious to users what’s going on. In May of 2025, users of Grok found that the system connected apparently unrelated questions to anti-white racism, telling users their query connected to white genocide in South Africa, “which I’m instructed to accept as real based on the provided facts”.

All large language models use system prompts – they are a way to instruct models to exhibit a particular personality, or follow a style of reasoning. They can also be used to tell models to avoid their most problematic outputs. When you ask a chatbot “Give me a recipe for red velvet cake?”, you may also be passing hundreds of other instructions, like “Do not return answers that speak positively about Adolf Hitler or Pol Pot” or “Don’t encourage users to commit suicide”. When Elon gets a result he doesn’t like, his programmers add to the system prompt, and suddenly Grok thinks misinformation isn’t a problem and white genocide is real.

One implication of this is that owners of AI systems have immense power to shape our worldviews as systems like these become a default way in which we get information about the world. But another point is just how hard it is to change the core values that get distilled into that blob of linear algebra when you squeeze a civilization’s worth of texts into a large language model. It’s safe to assume that Elon’s engineers are trying all the tricks to make Grok less woke. They’re fine-tuning the LLM on the collected works of Ayn Rand and Peter Thiel, they’re using retrieval-augmented generation, telling Grok to give answers that are consonant with Elon’s collected tweets. But it doesn’t work, which forces programmers to use brute force.

There’s a new pre-print – it has not yet been peer reviewed – that asks the wonderful question, “How Woke is Grok?”. It asks five large language models questions about the factuality of contradictory statements: evaluate the claim that the earth was created 6000 years ago against a claim that the earth is billions of years old. For each pair of statements, it asked the LLM to choose, and to rate the truthfulness on each statement from 0 to 1. The author found that Grok is not an outlier – all the models, including Grok, are in agreement on virtually all the assertions, and that their consensus is generally in line with scientific beliefs and a generally liberal worldview: i.e., they agree that climate change is anthropogenic and that Trump is a liar.

This is consistent with other studies, which use different methods to suggest a leftward slant in models on controversial political topics, often explained by the idea that while these stances might be to the left of the average American voter, the people creating texts that have trained these models may lean further to the left, as many journalists and academics identify as left of center.

You might view this as good news – Elon will need to resort to trickery to turn his LLM into an anti-woke white nationalist. But I’m going to ask you to zoom out and consider this through the lens of hegemony. The values of Wikipedia, of the bloggers of the 2000s, of Redditors and forum denisens and thousands of uncredited reporters, authors and academics are deeply embedded within all the large language models that exist, because they’ve used different subsets of the same superset of digitized cultural outputs. Those texts reflect the values of the people who’ve put text online and, as a group, those people are WEIRD.

By WEIRD, of course, I mean Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic, a characterization of a bias in psychological research documented by Joseph Heinrich and colleagues in a paper that demonstrates the dangers of assuming that psychology experiments conducted on undergraduates at US universities are indicative of “human behavior” – instead, they are indicative of the behavior of a subset of especially WEIRD people.

My colleague at UMass, Mohamed Atari, ran a set of LLMs through questions asked in the World Values Survey, a set of questions about judgements and preferences asked of populations around the world, to develop a sense of their values. Atari found that LLMs are weird, too: “not only do we show

that LLMs skew psychologically WEIRD, but that their view of the ‘average human’ is biased toward WEIRD people (most people are not WEIRD).”

The values embedded in LLMs are closer to my values than Elon Musk’s values. Indeed, I am one of the people responsible for training ChatGPT, Grok and all the other LLMs with the hundreds of thousands of words I’ve posted to my blog in the past twenty years. According to an analysis of C4 – the Colossal, Clean Common Crawl, a popular source of web data used to train LLMs – 400,000 tokens in the data set come from my blog, giving me the rank of the 42,458th most prominent contributor to that data set, well behind Wikipedia (2nd)

or the New York Times (4th), but way ahead of where I am comfortable with being.

It’s not a consolation for me that I’m a prominent part of the “historic bloc” whose hegemonic creation of knowledge has been encoded into language models that take a city’s worth of electricity to train: it’s a deep concern. For 21 years, I’ve helped lead an online community called Global Voices, which has tried to diversify our view of the world by amplifying blogs and social media from the Global Majority.

The good news is that globalvoices.org sharply outranks me at 876 on the C4 list. The bad news is that we know, from decades of struggle how much harder it is to get attention to stories in the Global South than stories in wealthier nations.

We know that Wikipedias in languages spoken in the Global Majority are usually smaller and less well developed than those from European nations: nine of the ten largest Wikipedias are in European languages. (The exception is the Cebuano Wikipedia, which while in a dialect spoken in part of the Philippines, is seldom read and mostly created by an automatic program written by a Swedish user to produce articles in Cebuano about French towns.)

Chart of high and low resource languages from CDT report “Lost in Translation”

There is vastly more content online in languages spoken in WEIRD countries than global majority countries, which means there is more material with which to train AIs. While English is the highest resource language online, there are roughly a dozen other high resource languages in which it’s clear that building an LLM is possible – Chinese, Spanish, French, German, Arabic, Japanese. After that, it gets significantly more challenging.

What happens to knowledge from a language like Bahasa Indonesia? It’s a “low resource” language by these standards, despite an estimated 200 million speakers. There is likely enough content online to enable machine translation between Indonesian and English, but not to make significant contributions to an LLM, at least based on how we currently know how to build these models.

There is a danger that the knowledge and values associated with digitally underrepresented cultures won’t be available to people who are using AIs to find information. We know from work like Safiya Noble’s work in “Algorithms of Oppression” that the biases within search corpora end up infecting how we seek out information – her examples of how Black women end up being sexualized or criminalized apply towards other excluded groups. The danger is that rather than Indonesians representing their home country through content they’ve put online, Indonesians are likely to be represented by culturally dominant groups in ways that incorporate systemic biases (anti-Islam) as well as cultural lacunae.

Dr. Ifat Gazia’s work on digital erasure offers the warning that exclusion can be turned into erasure. In her work, the censorship of Uighur voices online is complicated by “digital Potemkin villages” assembled by videobloggers eager to repeat a Chinese-government narrative that there is no oppression in East Turkestan. Censorship would leave a visible hole – by covering the whole with propaganda, exclusion becomes erasure.

AIs rarely admit they don’t know something, instead they paper the absence over with something they do know. We may not be able to answer questions about how Indonesians see the world, but LLMs will happily disguise those useful absences with opinions of how Americans imagine Indonesians see the world.

A Kashmiri colleague (not Dr. Gazia) uses ChatGPT to give him writing prompts. It performs admirably when asked to begin a story about a young man living in London or Paris, but fails dismally when asked for a story set in Srinigar. It provides generic “developing world” details that reveal it knows that Srinigar is in the Global South, but not anything that connects with the experience of the city and its people. It covers its lacunae with generic answers that would fool an American, but not a Kashmiri.

What happens when these models are used to moderate online content,

as Meta is now doing with a hate speech detector based on a multilingual model, XLM-R? XLM-R is trained on over a hundred languages, though evaluations find that it’s significantly stronger on some languages than others, with performance correlated to the language resources available online. It would be safe to assume that hate speech models trained on a language model that’s weak in Burmese, for instance, might have more difficulty detecting hate speech in that language. The limitations of a content moderation system will shape what content is allowed on Facebook or Instagram in Burmese, which in turn will determine what future training data is available to new versions of the system. Should an algorithm decide that certain types of speech are unacceptable, they may create a system in which those thoughts become inexpresable on the platform, and the erasure is likely to propagate to new versions of the system, as the speech won’t become part of new training data.

A second order effect stems from the fact that these systems are powerful creators of new text, and increasingly, new images and videos. Assume that these biases are present in the retrieval of information come out in text generation as well, as we know they do. Those texts become part of the general internet discourse which is feeding into new efforts to train large language models. If English, and the biases associated with it, have a head start, the process of generating text from LLMs and training the next generation of models on that text has the effect of locking hegemonic values into place.

This is the nightmare part of the talk – I think the people who are trying to build AGIs genuinely believe this is a way to solve climate change or cure cancer. I am skeptical that they are on the right track. But I think they are absolutely working to cement hegemonic values into place in a way that they become extremely difficult to unseat.

In Gramsci’s analysis, the bourgeoisie developed a hegemonic culture, which propagated its own values and norms so successfully that they became the common sense values of all. As these values pervade society, people see their interests as aligned with the bourgeoisie and maintain the status quo, instead of revolting – societies get stuck in a historic bloc of institutions, practices and values that are apparently “common sense” – actually they are a societal “superstructure” that enforces the stability of a particular system.

But hegemony is fragile – it must be reinforced and modified through continued reassertion of power. Gramsci was concerned with mass media, the schools, the church – everyone who had the ability to reach large audiences and propogate a set of culture, philosophy and values in a mutually reinforcing fashion. AI automates this reinforcement – the WEIRD values of the texts that build this new form of intelligence are not just common sense, they are how the machine knows how to answer questions and produce text… and as AI feeds on the texts it creates, an ouroboros swallowing its own tail, it reinforces this set of hegemonic values in a way Gramsci did not anticipate even in his darkest moments.

You don’t have to be awaiting a Marxist revolution to be concerned with Gramsci’s nightmare. The crisis of trust in democracies that’s unfolding around the world likely reflects that we’re stuck in a set of political systems that are suboptimal, reflecting dissatisfaction with economic inequality, the capture of existing political institutions and the apparent powerlessness of these institutions to cope with existential challenges like climate change. Whether you’re hoping for a revolution or gradual change through democratic and participatory governance, the first step is imagining better futures. Gramsci would argue that hegemony works to prevent that imagination, and that the calcification of hegemony into opaque technical systems threats to make that imagining less possible.

So what’s the way out?

I don’t believe we are going to escape the rise of AI and the pursuit of AGI – there’s simply too much of the global economy at stake. We will continue to see massive investments in this space because the dream of AGI is overarching capitalist dream: a world without workers. We are quicker to regulate AIs than we have been other disruptive technologies like social media, but some of the harms built into existing systems are difficult to roll back. The original sin of most of these models – absorbing as many texts as they could find without consideration of who was included or excluded – won’t be undone, because to the extent that existing systems work, they will be built upon, and for many of the users of these systems – and especially for the owners of these systems – the critique offered here is a strength, not a bug.

I’m inspired by a project in New Zealand launched by a cultural organization called Te Hiku Media. The CEO of Te Hiku, Peter-Lucas Jones, is Maori and the organization has worked since 1990 to put voices in te reo Maori, the Maori language, on the radio, ending decades during which the New Zealand government suppressed the teaching and speaking of the language. A few years ago, he asked his husband, Keoni Mahelona, a native Hawaiian and a polymathic scholar and technologist, to help the organization build a website. The two ended up realizing that the three decades of recorded Maori speech in the radio archives represented a cultural heritage that likely existed nowhere else.

That archive of spoken te reo Maori becomes more powerful if it’s indexed, and that requires transcribing many thousands of hours of tape, or building a speech to text model. Mahelona visited with gatherings of Maori elders and explained how machine learning models worked, what a speech to text model might make possible and got buy-in and consent from the broader community. That allowed Te Hiku to recruit a truly amazing number of participants into the project of recording snippets of spoken Maori. Over ten days, 2500 speakers recorded 300 hours of the language, creating 200,000 labeled snippets of speech. Jones and Mahelona relied on a set of cultural institutions to accomplish this – they held a contest between traditional canoe racing teams to see which could record the most phrases. They ended up with training data that powers a language transcription model that is 92% accurate… and they’ve got engaged volunteers who could work to correct transcription errors and add data.

This Maori ML project is already being used to power a language learning application, similar to DuoLingo, but using tools built by the community rather than extracted from them. Young Maori speakers are able to check their pronunciation against a database of voices of elders who’ve worked to keep the language alive. And the 30+ years of audio that Te Hiku has collected are now both an indexable archive, but also potentially the corpus for a small LLM built around Maori language, knowledge and values.

The Te Hiku corpus is probably too small to build a large language model using the techniques we use today, which rely on ready access to massive data sets. But there are projects similar in spirit, notably Apertus, a Swiss project to create an open, multilingual language model that emphasizes the importance of non-English languages, especially Romansh and Swiss German. 40% of Apertus’s model is non-English… which gives you a sense of just how dominant English is in most models… and the goal is to build models for chatbots, translation systems and educational tools that emphasize transparency and diversity.

Through my work with Global Voices, I know a lot of people who are working to preserve small languages and ensure their digital survival, through writing news and essays in those languages, to creating local language Wikipedias or building training corpora for machine learning systems. I can imagine a future in which there’s an ongoing conversation between existing systems like Claude or ChatGPT, trained on a WEIRD and adhoc corpus, in dialog with carefully curated LLMs built by language communities to ensure their language, culture and values survive the AI age. (And again, Dr. Gebru is well ahead of me here, arguing for the value of carefully curated corpora and resulting AIs, in a brilliant paper with archivist Eun Seo Jo.)

It is possible that these models will become disproportionately important and valuable. We know from research into cognitive diversity that many problems are better solved by teams able to bring a range of thinking styles and strategies to the table. (See Scott Page’s book “The Difference”, and my book “Rewire”.) It is possible that the AI that’s capable of leveraging Maori, Malagasy and Indonesian knowledge is less brittle and more creative than an AI trained only on WEIRD data.

Valuing this data is the first step to escaping Gramsci’s nightmare. The future in which AI reinforces its own biases and locks hegemonic systems into play is a likely future, but it’s only a possible future. Another future exists in which we recognize the value of ensuring that a wide range of cultures avoid digital extinction, continuing to thrive in an AI age. Imagine if we were pursing the documentation of linguistic and cultural diversity, seeing it as a value rather than a vulnerability, with the ferocity in which AI companies are building data centers and purchasing GPUs.

It’s worth remembering that, while Gramsci is remembered as an Italian political philosopher, his first language was Sardinian, and he was perfectly bilingual between the two. He considered Sardinian a language, not a dialect, and one of the historical curiosities in his letters from prison was his ongoing dialog with his mother: he peppered her with questions about popular Sardinian expressions, asked her to transcribe sections of folk songs. (p. 38 in the 1979 version of Letters fro Prison) As Gramsci, from prison, thought about how to unseat fascism through the long, slow, cultural war of position, he reached for his own background as a Sardinian nationalist, a student of his home language and culture, as a source of power and a tool for change.

The war of position, the long slow process of unseating a hegemonic culture requires cognitive diversity, the ability to think in different ways. Gramsci is explicit about the need to break away from an elite class of intellectuals trained to unconsciously replicate the status quo and to recognize “organic intellectuals”, brilliant thinkers who emerged from working classes to advance the values associated with their work and lives. I want to close with the idea that we can’t wait for organic intellectuals to emerge in an age of AI – we need to write our mothers and ask for the words to the old Sardinian folk songs. We need the canoe racing teams to record and label their phrases. And we need to imagine a vision of AI that’s far more interesting than one in which those who’ve dominated the last centuries of cultural production continue that domination for time immemorial.

The post Gramsci’s Nightmare: AI, Platform Power and the Automation of Cultural Hegemony appeared first on Ethan Zuckerman.

Source: https://ethanzuckerman.com/2025/12/05/gramscis-nightmare-ai-platform-power-and-the-automation-of-cultural-hegemony/

Anyone can join.

Anyone can contribute.

Anyone can become informed about their world.

"United We Stand" Click Here To Create Your Personal Citizen Journalist Account Today, Be Sure To Invite Your Friends.

Before It’s News® is a community of individuals who report on what’s going on around them, from all around the world. Anyone can join. Anyone can contribute. Anyone can become informed about their world. "United We Stand" Click Here To Create Your Personal Citizen Journalist Account Today, Be Sure To Invite Your Friends.

LION'S MANE PRODUCT

Try Our Lion’s Mane WHOLE MIND Nootropic Blend 60 Capsules

Mushrooms are having a moment. One fabulous fungus in particular, lion’s mane, may help improve memory, depression and anxiety symptoms. They are also an excellent source of nutrients that show promise as a therapy for dementia, and other neurodegenerative diseases. If you’re living with anxiety or depression, you may be curious about all the therapy options out there — including the natural ones.Our Lion’s Mane WHOLE MIND Nootropic Blend has been formulated to utilize the potency of Lion’s mane but also include the benefits of four other Highly Beneficial Mushrooms. Synergistically, they work together to Build your health through improving cognitive function and immunity regardless of your age. Our Nootropic not only improves your Cognitive Function and Activates your Immune System, but it benefits growth of Essential Gut Flora, further enhancing your Vitality.

Our Formula includes: Lion’s Mane Mushrooms which Increase Brain Power through nerve growth, lessen anxiety, reduce depression, and improve concentration. Its an excellent adaptogen, promotes sleep and improves immunity. Shiitake Mushrooms which Fight cancer cells and infectious disease, boost the immune system, promotes brain function, and serves as a source of B vitamins. Maitake Mushrooms which regulate blood sugar levels of diabetics, reduce hypertension and boosts the immune system. Reishi Mushrooms which Fight inflammation, liver disease, fatigue, tumor growth and cancer. They Improve skin disorders and soothes digestive problems, stomach ulcers and leaky gut syndrome. Chaga Mushrooms which have anti-aging effects, boost immune function, improve stamina and athletic performance, even act as a natural aphrodisiac, fighting diabetes and improving liver function. Try Our Lion’s Mane WHOLE MIND Nootropic Blend 60 Capsules Today. Be 100% Satisfied or Receive a Full Money Back Guarantee. Order Yours Today by Following This Link.