Indigenous Communities Near Panama Canal Have a Bigger Problem than Trump

8 May 2025 (openDemocracy)* — Since entering office in January, Donald Trump’s repeated threats to seize control of the Panama Canal, a critical passage for global freight traffic, have dominated headlines around the world. | ESPAÑOL

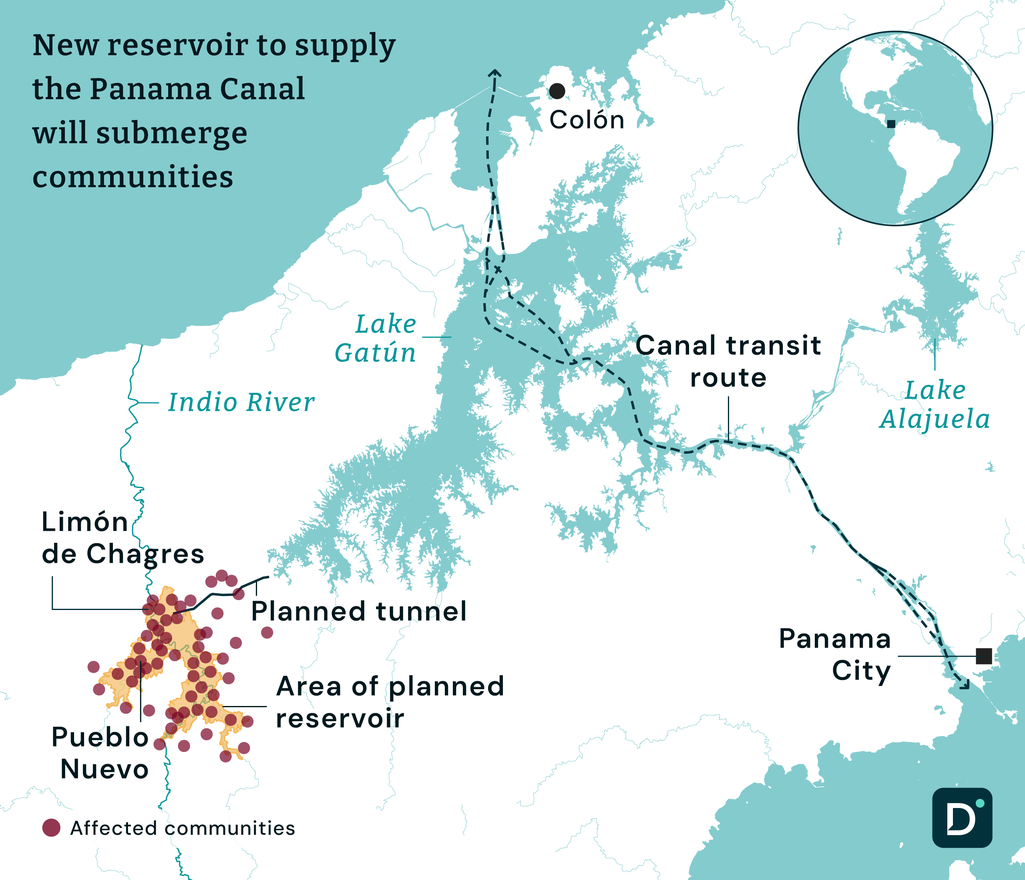

But two hours west of Panama City, 12,000 locals have a more pressing concern: their government plans to flood their lands and relocate them to create an artificial lake to ensure water supply to the canal.

“Tell the president to leave us alone. Does he know everything we are going to lose: the land, the crops, the homes? We are worried,” says Elizabeth Delgado, a resident of Limón de Chagres, a community on the banks of the Indio River that is the focus of the planned damming project.

Along the river, the Delgados and roughly 500 other families face seeing their homes submerged.

The Panama Canal is a artificial waterway that cuts across the Central American country to connect the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean.

Proposals for the reservoir project have come after decades of gradually increasing freight traffic transiting through the canal, which now handles around 5% of global maritime trade and reported revenues of around $5bn for the 2024 financial year.

The route is particularly crucial for the US, with around 40% of the country’s container traffic travelling through the canal each year.

As the canal’s traffic has grown, prolonged droughts have hampered its operations.

In 2023, a drought driven largely by the El Niño weather phenomenon forced the Panama Canal Authority (ACP, a public and autonomous agency) to reduce the number of ships travelling through the waterway for the first time in history, with daily passages dropping from the maximum capacity of 37 to 22.

While scientists are still understanding the relationship between climate change and the El Niño phenomenon, emerging evidence suggests rising temperatures might lead to stronger El Niño events.

The disruption continued into the first months of 2024, when water levels in the canal system reached historic lows and the interoceanic route operated at just 63% of its normal capacity, according to Jorge Luis Quijano, a former ACP administrator.

The Panama Canal system is made up of a series of waterways and locks connecting the country’s two coastlines via two artificial lakes: Gatún, which was created by the damming of the Chagres River, and Alajuela.

Each ship passing through the canal requires 52 million gallons to navigate this system of locks.

But the two lakes also supply water to just over half of Panama’s total population of 4.5 million, including the residents of the cities of Panama, Arraiján, La Chorrera and Colón.

The drought of 2023-24 led to such low water levels in these lakes that the water supply to local people became challenged in order to ensure the continued transit of ships.

The drought and restrictions have not only hit Panama’s income, but have forced shipping companies to look for alternative routes, including the Suez Canal, with rising costs, delays and carbon emissions.

Facing uncertain projections over future droughts and rainfall, a plan was unveiled to increase the canal’s water capacity by building a dam to create a reservoir on the Indio River covering around 4,600 hectares.

Construction of the planned dam, which has yet to receive approval from affected communities, is slated to begin in 2027 and will take four years, followed by two years to fill the reservoir. Whether or not this approval is legally required for work to begin is disputed.

The dam is estimated to cost $1.5bn, with an additional $400m reportedly allocated for compensation for relocated residents and social projects.

Data Source: Panama Canal Authority / Map: Dialogue Earth

“We estimate that there are around 2,000 citizens who could be directly affected by this project, although the entire Indio River area has approximately 12,000 people,” the ACP’s administrator, Ricaurte Vásquez, recently told a press conference.

Some 12,000 people live in the Indio Basin, most of whom rely on the land to survive. All will be affected by the construction of a dam, regardless of whether their homes are the ones flooded, although most will seemingly not be eligible for compensation.

A community fears for future

Two hours’ drive from the Panamanian capital, the road to the Limón de Chagres community in the province of Colón is littered with hand-painted signs that reflect the local sentiment.

“Ríos sin presas, pueblos vivos” (Rivers without dams, living towns), “Respeten nuestra tierra” (Respect our land), and, perhaps most directly, “No a los reservorios de río Indio” (No to reservoirs on the Indio River).

The ACP has been surveying the affected areas and attempting to consult with the residents of the communities that stand to be impacted by the project, after a 2006 law blocking the creation of a new reservoir was last year overturned by the Supreme Court.

The ruling gave the ACP control over water resources beyond the canal’s watershed boundaries – which had previously been restricted – opening up the possibility of the construction of the Indio River reservoir.

This year, the first actions will be taken. Many residents lack official titles for their properties, and the government is looking to assist in formalising these documents to enable payment for the lands of those affected and their relocation.

At this first stage of dialogue with communities, no estimated date for the bidding process for construction contracts to build the dam has yet been released.

Upon completion of the dam, the surface of the Indio River would expand to form a reservoir covering areas across three different provinces along the river’s current 98-kilometre course.

The project also includes a pipe to transfer water to the Panama Canal basin, where Gatún and Alajuela lakes are located.

The ACP has insisted that the process will be carried out in dialogue with those affected, offering guarantees of better living conditions. It says the reservoir will guarantee both the supply of water for the population and the operation of the canal for 50 years – a claim disputed by the plan’s critics.

Despite such promises, there is visible tension and anger in the areas in line to be flooded. To reach some communities during our reporting trip, we needed to travel by canoe, then walk along dirt paths, mud often reaching our knees.

On one such occasion, when visiting Pueblo Nuevo, another community threatened by the dam and eviction, we heard voices coming from a house on top of a hill.

“Go look for something else to do!” and “We don’t want you coming through here,” local people shouted, as a young Indigenous man on a horse came out to meet us on a track leading down from the houses.

On one side, pasted on a weathered wooden gate, was a handwritten note that read: “No entry to the ACP – private property – we will not grant the social license.” The sign drew our attention to another, with a drawing resembling a gun next to the word “danger”.

We introduced ourselves to the horse rider as reporters from Dialogue Earth and explained that we were looking for information, to which he responded that “journalists have sold out” and that they didn’t want “dialogue”.

Only after we explained we were reporting for an international media outlet, he finally agreed to talk.

“The ACP administrator, Ricaurte Vásquez, said that 90% of the community is in favour of the flooding, which is false,” said the Indigenous rider, Abdiel Sánchez, a 28-year-old resident of Pueblo Nuevo.

Once these initial differences were overcome, the community invited our team to join a group celebrating the birthday of a six-year-old girl.

That they had delayed the party in order to go flyposting in the local area – putting up posters and materials demonstrating their opposition to the reservoir – perhaps offers some indication of the strength of this rejection.

Among those present was Artemio Sánchez, a 52-year-old farmer and president of the local social development board, who said that they do not get any “help from the government, much less from the canal [authority], not even ten cents to buy a box of matches.”

Locals also told us that they rarely encounter the authorities, so every time they see a stranger in the area, there is a paranoia that it may be an ACP official who is doing a census of the communities, as they are aware that the first property titles will be handed out in 2025.

“We were yelling at you because we thought you were from the ACP, because we do not agree that they walk around our area and river without permission taking photos of the school and the churches, knowing that we do not agree,” explained Sánchez.

“If the project happens, we hope that we are not left hanging,” said Nery Saenz, another of the party guests. She recalled the building of Gatún Lake, which affected many families: “Nothing was recognised, and their lands were taken away… but to this day, they’ve received nothing.”

“We’re afraid this situation will repeat for us,” Saenz told us.

Gatún Lake reached full capacity in 1913 to enable the canal’s first operations. Records show that the first evictions of populations near the waterway took place in 1912, when the Panama Canal Zone was under US control, following a decree issued by then-US president William Taft for the construction of Gatún, which was the world’s largest artificial lake at the time.

Sources such as historian Marixa Lasso’s Erased: The Untold Story of the Panama Canal have described the US government’s actions in regard to the evictions at the time as being based on racist prejudices against a mostly African-descendant population, and on its own military and national security objectives.

Land and life in the community

Elizabeth Delgado lives in a painful situation of uncertainty. She says she has had trouble sleeping ever since she heard about the proposal to flood the area to create the reservoir, around three months before our visit in November.

Elizabeth Delgado gathers water from a storage tank in Limón de Chagres. The community’s residents collect their water from the Indio River, as there is no other potable source | Pich Urdaneta / Dialogue Earth

“We make our living off the land,” Delgado told us, standing at the door of her wooden house, its white paint chipped and weathered.

She lives with her husband and seven children, and given the lack of jobs in the area, they subsist on planting and harvesting the ñampí yam, cassava, chilli, cilantro and onion, among others, as well as raising chickens. She has lived in Limón de Chagres for more than 18 years.

The Indio River is their natural source of water, since there is no service for potable water in the area. The residents of the basin extract water from the river or streams by pipes, search for it in wells, or walk long distances with filled buckets and pots. There is even less electricity and other basic services.

With everything that is happening, the children are afraid, says teacher Aurelia Castillo, who for the past nine years has cared for the children who attend school in Pueblo Nuevo.

Castillo said local sixth-grade students travel to the nearby town of Coquillo for their schooling. That town, too, is expected to be submerged. With a sad face, she asked: “Where are we going to go to study with our children?”

Environmental impacts and alternatives

The Indio River is part of the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor, a key ecosystem that connects various areas of Central America and southern Mexico, and is a refuge for species such as monkeys, crocodiles and various endemic plants.

This ecological corridor stands to be severely fragmented by the construction of the reservoir.

Isaías Ramos, a biologist at CIAM Panama, an environmental civil society organisation, said the potential impact of flooding the area to build a new lake is significant, but the social effects would be even more serious.

He added that many communities have not yet been sufficiently informed about the project, despite this being mandatory under the Escazú Agreement, the Latin American and Caribbean treaty that promotes transparency and access to information in environmental issues, which Panama ratified in 2020.

The ACP has published reports of multiple meetings with Indio River residents, saying it has maintained “permanent contact” and listening mechanisms with communities, having held over 40 meetings with around 2,000 residents as of September 2024.

Although water is abundant in the Indio River as a whole, its flow is decreasing in some areas, making transportation difficult.

Guillermo Torres, the president of the National Water Council (Conagua, a governmental body that guides water security policies), has claimed that the Indio River project would not guarantee increased water for the 50 years the ACP promised.

Instead, he says, it will offer only a temporary solution due to seasonal fluctuations in rainfall and the possibility of other droughts impacting the reservoir’s capacity.

This has led Conagua to propose an alternative to the Indio River reservoir: channelling water from Lake Bayano, 100 kilometres east of Panama City. The pipeline from Bayano, Torres claimed, could guarantee water until 2075, offering a longer-term solution.

The Limón de Chagres and Pueblo Nuevo residents Dialogue Earth spoke with also expressed a preference for the Bayano pipeline, which they say would be less disruptive to the ecosystem and their communities as it does not require a dam, only a pipeline from an existing artificial lake, and would not involve evictions.

They strive to preserve the Indio River and its surroundings, valuing the tranquillity and untouched nature it provides them.

The ACP is also considering other reservoirs, such as those on the Coclé del Norte River in the country’s central region, and the Caño Sucio River, in the west.

For now, though, the ACP is attempting to continue seeking approval from local communities, having approved the project on 21 February and concluded its census of the Indio River at the end of April.

Discussions are likely to remain challenging, with recent protests sending a further signal of communities’ continued resistance.

*This is an edited version of an article first published by Dialogue Earth

*SOURCE: openDemocracy. Go to ORIGINAL: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/panama-canal-new-resevoir-flood-indio-indigenous-communities-donald-trump-us/ 2025 Human Wrongs Watch

Source: https://human-wrongs-watch.net/2025/05/12/indigenous-communities-near-panama-canal-have-a-bigger-problem-than-trump/

Anyone can join.

Anyone can contribute.

Anyone can become informed about their world.

"United We Stand" Click Here To Create Your Personal Citizen Journalist Account Today, Be Sure To Invite Your Friends.

Before It’s News® is a community of individuals who report on what’s going on around them, from all around the world. Anyone can join. Anyone can contribute. Anyone can become informed about their world. "United We Stand" Click Here To Create Your Personal Citizen Journalist Account Today, Be Sure To Invite Your Friends.

LION'S MANE PRODUCT

Try Our Lion’s Mane WHOLE MIND Nootropic Blend 60 Capsules

Mushrooms are having a moment. One fabulous fungus in particular, lion’s mane, may help improve memory, depression and anxiety symptoms. They are also an excellent source of nutrients that show promise as a therapy for dementia, and other neurodegenerative diseases. If you’re living with anxiety or depression, you may be curious about all the therapy options out there — including the natural ones.Our Lion’s Mane WHOLE MIND Nootropic Blend has been formulated to utilize the potency of Lion’s mane but also include the benefits of four other Highly Beneficial Mushrooms. Synergistically, they work together to Build your health through improving cognitive function and immunity regardless of your age. Our Nootropic not only improves your Cognitive Function and Activates your Immune System, but it benefits growth of Essential Gut Flora, further enhancing your Vitality.

Our Formula includes: Lion’s Mane Mushrooms which Increase Brain Power through nerve growth, lessen anxiety, reduce depression, and improve concentration. Its an excellent adaptogen, promotes sleep and improves immunity. Shiitake Mushrooms which Fight cancer cells and infectious disease, boost the immune system, promotes brain function, and serves as a source of B vitamins. Maitake Mushrooms which regulate blood sugar levels of diabetics, reduce hypertension and boosts the immune system. Reishi Mushrooms which Fight inflammation, liver disease, fatigue, tumor growth and cancer. They Improve skin disorders and soothes digestive problems, stomach ulcers and leaky gut syndrome. Chaga Mushrooms which have anti-aging effects, boost immune function, improve stamina and athletic performance, even act as a natural aphrodisiac, fighting diabetes and improving liver function. Try Our Lion’s Mane WHOLE MIND Nootropic Blend 60 Capsules Today. Be 100% Satisfied or Receive a Full Money Back Guarantee. Order Yours Today by Following This Link.